Test Proven Design

test

design

programming

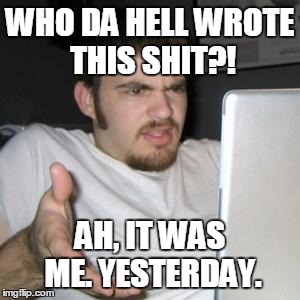

Just a couple of days ago, I was surfing through the code base of the project I am actually working on when I found something that disgusted myself a lot.

void execute(Info info, State from, State to) {

Action action = chooser.getAction(from.isInfoForSimpleAction() ? 1 : 0,

to.isInfoForSimpleAction() ? 1 : 0);

if (action != Action.NOOP) {

try {

final Message message = Message.newBuilder()

.setAction(action)

.setOutput(new OutputWrapper(info).getOutput())

.setParticularState(to.isAParticularState())

.build();

producer.sendWithReturn(info.getId(), message);

} catch (IOException e) {

// Omissis.

}

}

}I smelled that something was wrong. Then, I checked unit tests associated to the class.

@Test

public void executeShouldSendAnAcceptMessage() throws Exception {

// In case of Action.ACCEPT

// Omissis.

}

@Test

public void executeShouldSendRevertMessage() throws Exception {

// In case of Action.REVERT

// Omissis.

}

@Test

public void executeShouldNotSendAnyMessage() throws Exception {

// In case of NOOP

// Omissis.

}The value of Action influences two aspects in our class: the construction of the message and

then sending process. Is it correct? Moreover, what if one day the construction process will become

more complex? Unit tests number will increase exponentially, due to combinatorial calculus.

Not so good.

Let’s look how tests analysis can improve the architecture of software that we develop everyday.

The very beginning

So, which is the main problem with the above code? First of all, we have to understand what the

code is meant to do. Basically, the method execute takes some data modeled as the Info object

and a couple of states, from and to. Using this last information, it decides the Action to

take and finally envelops this action into a Message that will be send using probably a

Kafka producer.

There are many operations involved for a single method, aren’t there? To choose the action some

algorithms is performed on from and to states. Then, using the result of such logic, an object

of type Messageis built.

The main question is: how can I test that given the triplet (info, from, to) the right Message

is built? All the logic is drowned inside the execute method.

Let’s try to change some stuffs in order to obtain a better (a.k.a. more testable) design.

The root of evil

Reviewing the responsibilities owned by the execute method, we found that it owns more than one.

The responsibilities that I see are the following:

- Building a message from its input data

- Publishing of the message on a Kafka topic

So, if the algorithm that derives a message starting from the triplet (info, from, to) changes,

the execute method must change accordingly. Moreover, if also the method that we use to

publish the message changes, the execute method must be changed too.

What is worse is that the creation of the message is a process that is all internal to the method. We do not have any chances to unit test it (unless we use some advanced feature of Mockito)!

How can we repair such a bad situation? Once, Romans would have said

divide et impera.

And also I do.

The path through perfection

There is a principle in SOLID programming which is known as Single-Responsibility Principle. It represents the first “S” in the word SOLID. This principle states that

A class should have only one reason to change.

It is one of the more quoted principles of “Uncle Bob” Martin. Whenever you do not know what to say, quote the SRP ;) However this time it seems to be the right principle to use.

We saw that the execute method owns two responsibilities, that correspond to two different axis of

change. Following the principle we should refactor the method (or better, the class that owns the method)

so that it will contain only a single responsibility.

// Stupid name for this class, but I cannot think to something better right now :P

class MessageFactory {

final ActionChooser chooser;

Optional<Message> buildMessage(Info info, State from, State to) {

Action action = chooser.getAction(from.isInfoForSimpleAction() ? 1 : 0,

to.isInfoForSimpleAction() ? 1 : 0);

if (action != Action.NOOP) {

final Message message = Message.newBuilder()

.setAction(action)

.setOutput(new OutputWrapper(info).getOutput())

.setParticularState(to.isAParticularState())

.build();

return Optional.of(message);

}

return Optional.empty();

}

}

class Executor {

final MessageFactory factory;

void execute(Info info, State from, State to) {

Optional<Message> maybeMessage = factory.buildMessage(info, from, to);

maybeMessage.ifPresent(m -> {

// Something better can be done here

try {

producer.sendWithReturn(info.getId(), m)

} catch (IOException e) {

// Omissis.

}

});

}

}Basically we moved the responsibility relative to construction of Message type in a dedicated type. This

lets us to put a better focus on each resource and to control better the evolution and maintenance of each

type.

New unit tests for MessageFactory lacks. The smart reader will easily overcome this problem ;)

Test Proven Design

Should we have come to the same conclusion following another path? The answer is yes. We already stated

that tests of the original component were not perfect. The construction logic of a Message type was

not properly tested, due to the lack of visibility of this process.

Trying to solve this problem, we reasoned about the structure of the class, in terms of responsibility. We found that the class owned two different reasons to change. Following Robert C. Martin’s SOLID principles, this means that the class does too much.

Finally, we brought outside the original class one of the two responsibilities, obtaining code that was improved from different points of view.

Summarizing, following a need deriving from the testing process, we came to a design that seems to be good enough.

Conclusions

Starting from a “real life” code snippet, we saw how the absence of some unit test drove us to the refactoring of a class. The new version of the class also satisfies one of the basic principles of SOLID programming, the Single-Responsibility Principle. This means that the class is more maintainable, flexible, coherent, and so on.

Probably using Test Driven Development (TDD) the results would have be the same. Unfortunately, despite of my knowledge of the theory of TDD, I never had the opportunity to apply it in real life. I firmly believe that the effective application of TDD principles should be taught initially. Is there anybody out there who can confirm it?